In four decades, I have built numerous computer and web products. I started as a kid and never looked back. Until recently, someone convinced me to make this list.

Introduction

40 years ago, I discovered the future.

I remember the sound first: a synthetic voice, mechanical and slightly wobbly, reading out words a technician had just typed.

As a kid, I thought I’d become a pianist (I started at four) or maybe a historian (I had a childhood obsession with the Etruscan civilization). Then one day, I stumbled upon a computer that could talk.

It was during a school trip to a science exhibition. I think the machine was called Videolog, but I’m not even sure anymore.

A technician in a white coat was typing lines on a keyboard, and the computer would speak them out loud. For me, in 1978, it felt straight out of an Asimov book. While the rest of my class was fascinated by some animation at the other end of the booth, I couldn’t look away from that machine.

Seizing a moment when no one was watching, I started typing “hello Tariq.” Just as I was about to hit Enter, I felt a sharp pinch on my right ear. My teacher was pulling it, yelling: “Don’t touch anything, you’ll break it!”

The technician looked at the screen. Instead of scolding me, he smiled, a smile I read as “Welcome to the club.”

A club it would take me a few more years to join.

In 1982, my father bought me a Texas Instruments TI-99/4A that plugged into the family TV. A frustrating setup. Like thousands of kids my age, I had to fight for screen time with the rest of the family. Saving my work on cassette was a nightmare, so most of my programming happened on paper.

My father had it easier. His university gave him an Apple II+, a modem, and a subscription to an early online service, The Source. He could access specialized American databanks, forums, news feeds, and even a gateway to ARPANET, the ancestor of the Internet.

I learned to use it when he wasn’t around, exploring the world of networks. A new universe opened up for me. I remember hanging out in my first forums in English, dictionary in hand.

As I navigated deeper into online services, I discovered the world of warez (software you could just copy) and the computing underground. A culture that only existed in online publications, a counter digital culture that spoke to me instantly. Later, that was expressed in the demo scene, incredible mini programs attached to pirated software. Sometimes you would get the software just to get the chance to see them.

One of the heroes of this generation of 80’hackers was Wau Holland, the cofounder of the Chaos Computer Club, a German hacker group. His utopian, political vision of computing was something extremely unique. And resonated deeply.

He painted a vision of a future 20 years ahead, where everyone would have free access to information. Looking back, I believe it was the foundation of a European approach to technology: information should be a public infrastructure accessible to everyone. A dream that would be undermined by the privatisation of major European telecom operators in the late 90s.

But what I’ve learned as a kid was that the 80’s online revolution was happening in the middle of a very sophisticated Cold War battle. A battle that is still going on today.

In 1984, most of us discovered the existence of the most secretive intelligence agency, the NSA, in the book Kids and the tv show Whiz Kids, (episode 10). Through via hacker magazines distributed via online bulletin boards, we also learned how the KGB hacked its way into the Pentagon using German hackers as a proxy (Karl Koch).

I was 12, and I needed to find my path. An unlikely encounter at my middle school gave me the chance. To cross over to the other side. To build my own server instead of just being a user.

Product portfolio (1984-2015)

The nascent computer culture of the 80s, the first BBSs, hacking, the early Web, and its rebirth a decade later as Web 2.0, all of it was an incredible playground for building products.

A Philosophical Approach to Software

The philosophy of the software pioneers of the 70s runs deep in my products. Studying Doug Engelbart and Alan Kay taught me about form and function, the integration of software and hardware, and how to make software less intrusive so that user intuition can take over.

Think Muji but for Software

My three rules for product design:

- No logo (the product belongs to the user)

- A calm, peaceful UX (to fit seamlessly into daily life)

- An easy way for users to take their data and leave (data portability)

I’ve been lucky enough to pioneer several ideas that are now part of the digital landscape: personalized widgets, and the first netbook (a laptop under €200) running a web-based operating system, with seamless cloud synchronization.

I’ve divided this portfolio into three eras:

- The pre-Internet network era in Europe

- The early consumer Internet and its creative chaos

- The startup era, Web 2.0, and the cloud, which gave my work international visibility

Pre-Internet Era

(1984-1995)

In 1984, I discovered I could build my own Minitel server using the home computer. Then I got kicked out of the school newspaper for criticizing the government’s “Computing for All” plan. That’s when I understood: technology is also political.

Electre BBS (1984)

My neighborhood had been selected for the Minitel experiment. It became the second modem in the house (my father, an economist, already had access to American online services). With a friend from school, I built my first online server using his Commodore 64 and my Minitel.

This was my first experience designing an interface. Years later, I learned that a similar commercial service had existed in the US on the Commodore 64. It was called PlayNET, the ancestor of America Online.

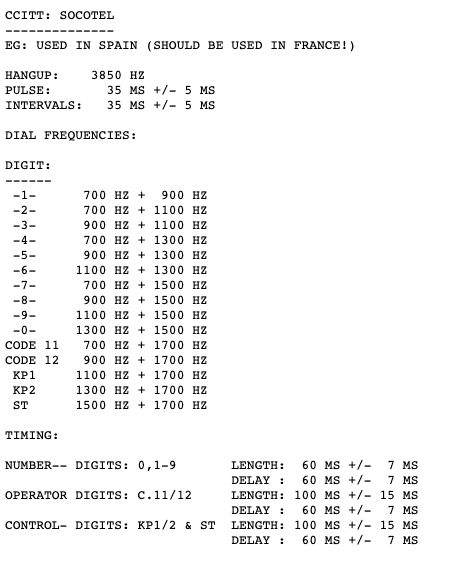

T Blue Box (1991)

Long before free long-distance phone calls, one of the favorite hobbies of computer geeks was finding ways to connect to internal online services for free.

Europe was on a different system, and until someone named Guru Josh, it was hard to find a frequency working in France. I just had to build my T blue box and experiment the « phoneverse.»

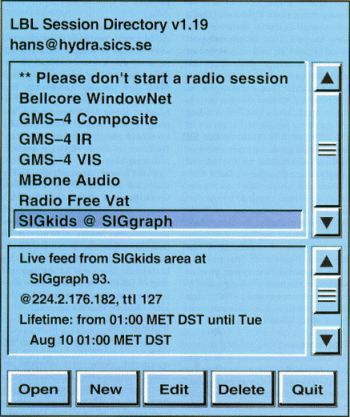

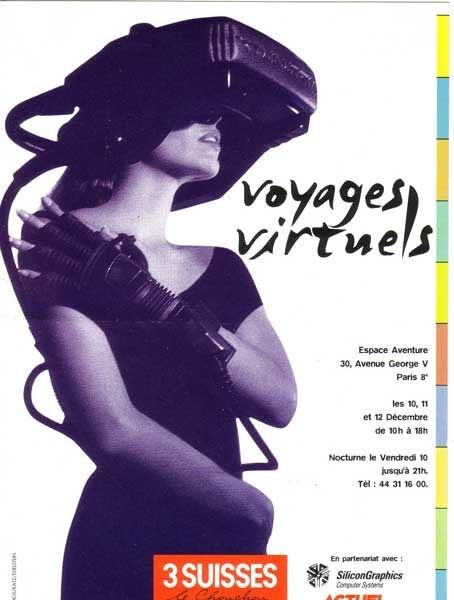

Unnamed Mbone Pirate Radio (1993-95)

One of the early Internet revolutions was Multicast, the ability to stream audio and video in real time across the network. At the time, the tech was experimental, used mainly by NASA and MIT.

I used it to run a continuous electronic music radio station, feeding a DAT player into a Sun Unix workstation. My audience was tiny, but I know I had listeners. The sound quality was not great, but I love the idea of using a network to « stream « music until an MIT sysadmin told me to shut it down.

I still remember what he said to me: “Streaming music over the Internet is a stupid idea with no future.”

Glad I didn’t listen.

Radio Nova (1993-1995)

When I joined Radio Nova, I found myself among an editorial team unlike any I’d known. Jean-François Bizot took me under his wing. We had a deal: he’d show me the secrets of underground culture, and I’d introduce him to this nascent thing called the Internet.

What followed were countless late-night conversations with John Perry Barlow, cyberculture guru; Timothy Leary, the LSD prophet turned VR evangelist; Hakim Bey (whose Temporary Autonomous Zones inspired Burning Man); and Kevin Mitnick, the legendary hacker. I was suddenly at the heart of a new movement. By day at university, I studied computer science; by night, I discovered its culture on The WELL BBS.

The Early Days of Consumer Internet

(1995-1999)

Nirvanet (1993-1996)

Alongside Radio Nova, I helped Christian Perrot (the first editor-in-chief of Nova Magazine) and Marie France Perez to create one of the first web portals dedicated to digital culture. I introduced them to the tech underground and made a few connections, including with the French writer Maurice Dantec and his prophetic novel “Les racines du mal.” The site became a cult classic, but got lost in the chaos of the first Internet boom. Relaunched several times, it eventually vanished.

Les Technochroniques (1993-2005)

A blog before blogs existed. I had kept the habit of sharing content online. I was very sporadic at first, until French Newspaper Le Monde asked me to become one of their official bloggers. In 2004, I covered how technology was used during the US presidential election. My most-read piece at the time? “ Are blogs: The New CB Radio of the Web?”

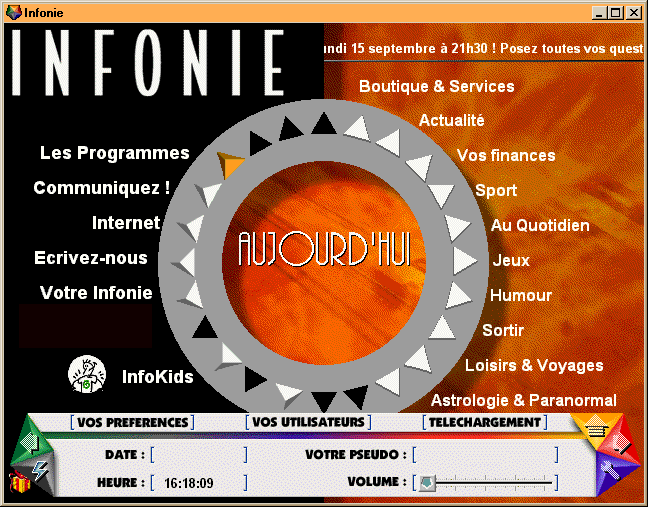

Infonie (1995)

I needed an internship. I was interviewing for the Vidéothèque de Paris, an incredible video library where you could view films on demand. I convinced the director that they should turn their old video cassette archive into a digital video-on-demand platform (which the Forum des Images, its successor, would finally build 15 years later). But the CTO at the time did not believe in the Internet, so I was again on the marketing urgently needed an internship.

Not a lot of people understood the Internet in France, as the culture of Minitel (France's official online service at the time) was entrenched. But after demoing the very first Netscape at the Interop trade show, I immediately landed a spot in the IT department at Infonie, an online clone of AOL founded by Bruno Bonnell and Christophe Sapet. Being a fan of their books on TI99/4 helps too.

A few days in, I realized Infonie had no plans to offer real Internet access, as users were locked into their proprietary system. I asked my internship manager and new mentor, Franklin Bohbot, if I could hack a quick Internet gateway just in case.

want

When the CTO refused to give me access to the main servers, I installed Linux on my desktop, added two network cards, and started building a bridge between Infonie and the Internet.

A developer from the Lyon office got curious and helped me write my first Linux driver. On the advice of my friend Benjamin Ryzman, I used a new technique at the time called IP masquerading, which let me route an entire network through my single machine.

I eventually convinced the "design" team to add an “Internet” button to the interface that would point users who want it to access the network via my little office Dell.

On launch day, as I expected, most users rushed straight to the Internet and ignored the proprietary services. The good news is that my little setup held up beyond expectations.

The next day, the CTO who had dismissed my project decided to take it over and move it to a shiny new Sun supercomputer. He also offered me a job.

I politely declined as I only dreamed of one thing: working with the people who create things, not those who just use.

A year later, I got my wish, an internship at OpenTV, a joint venture between Thomson and Sun, in the heart of Silicon Valley. That’s where I learned the craft, and where my creative instincts were finally respected. John Gage, who was the Chief Scientist of Sun back then, allowed me to access an early prototype of the Java computer. A small computer in 1996 introduced me to an even bigger idea that would change everything: the cloud.

Minirezo and REZO.net (1996-1999)

With a small crew of independent web creators called Le Minirézo (Mona Chollet, David Dufresne, Les Ours, Le Menteur, Arno, and others), we wrote the Independent Web Manifesto. I proposed creating Rezo.net, meant to be the underground French Yahoo. It’s since been taken over by another team.

PERDU.COM (1996)

I created perdu.com with Gilles Boccon-Gibod. I came up with the domain name; he instantly came up with the content.

N@RT (1999) first online auction ever

With N@rt, a French company, and Maître Binoche, one of France’s most famous auctioneers, we launched the first online art auction at Drouot. The first sale was a collection of Dreyfus manuscripts. The second was a selection of Man Ray photographs. We used an experimental Java computer lent by Sun Microsystems to record bids in real time.

Génération MP3 (1999-2007)

In 1999, I launched France’s first tech blog about digital music. Originally called mptrois.com, it became Generationmp3. The tagline: music after the CD.

The Startup, Web 2.0 and Cloud Era

(1999-2015)

After years of writing, coding, and designing for others, I finally decided to go solo, just as the Internet bubble burst.

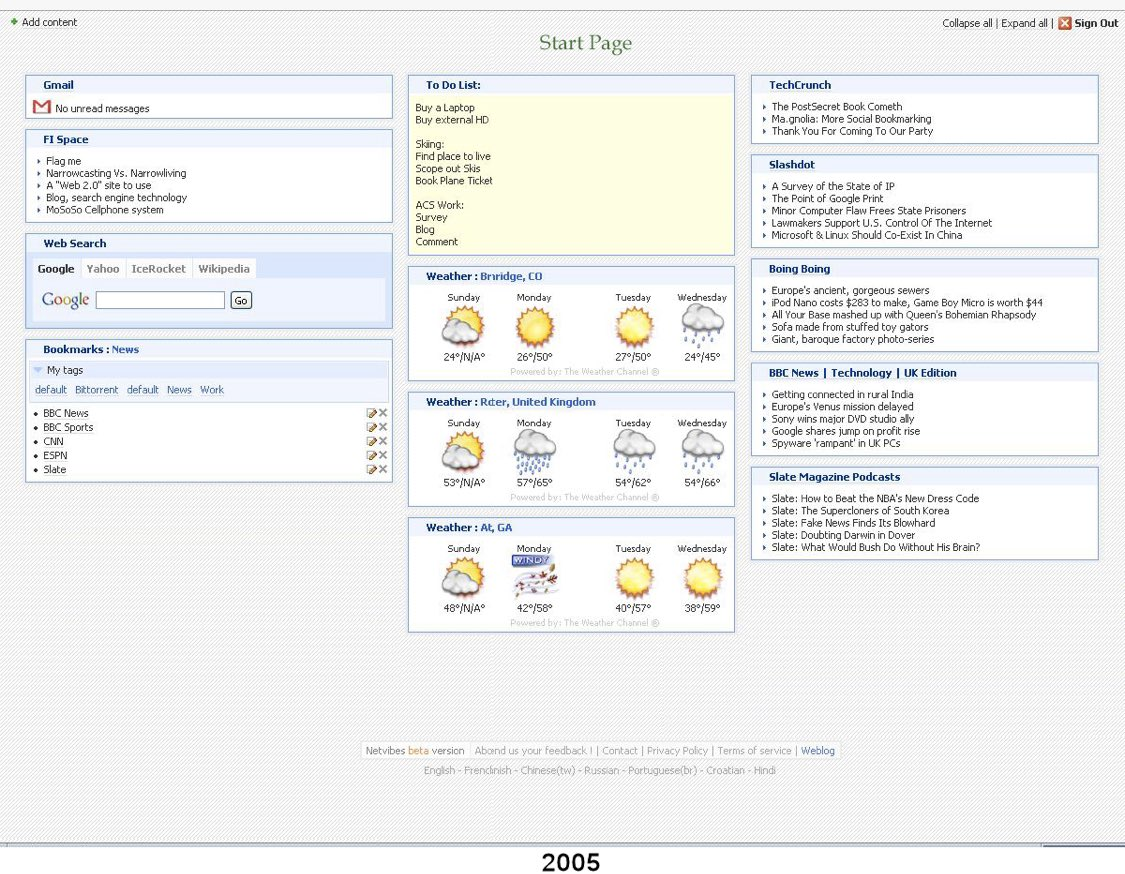

Netvibes (2005)

Netvibes pioneered the personalized homepage. As a blogger and obsessive reader, I could see we were all about to drown in content. Netvibes lets users curate their own stream of automatically updated content.

The first version launched from a Parisian café called La Fée Verte. The service grew into the third most popular start page in the US. It was used in over 150 countries and served half a billion widgets in 2008. It was also one of the first products to integrate the early Facebook API.

I wanted to evolve the product into a social and mobile platform. My sales team and investors wanted to sell a dumbed-down white-label version. Turning a beloved consumer product into a generic B2B tool seemed like a terrible idea. I left in April 2008 to start Jolicloud.

Netvibes remains one of the most celebrated French startups ever.

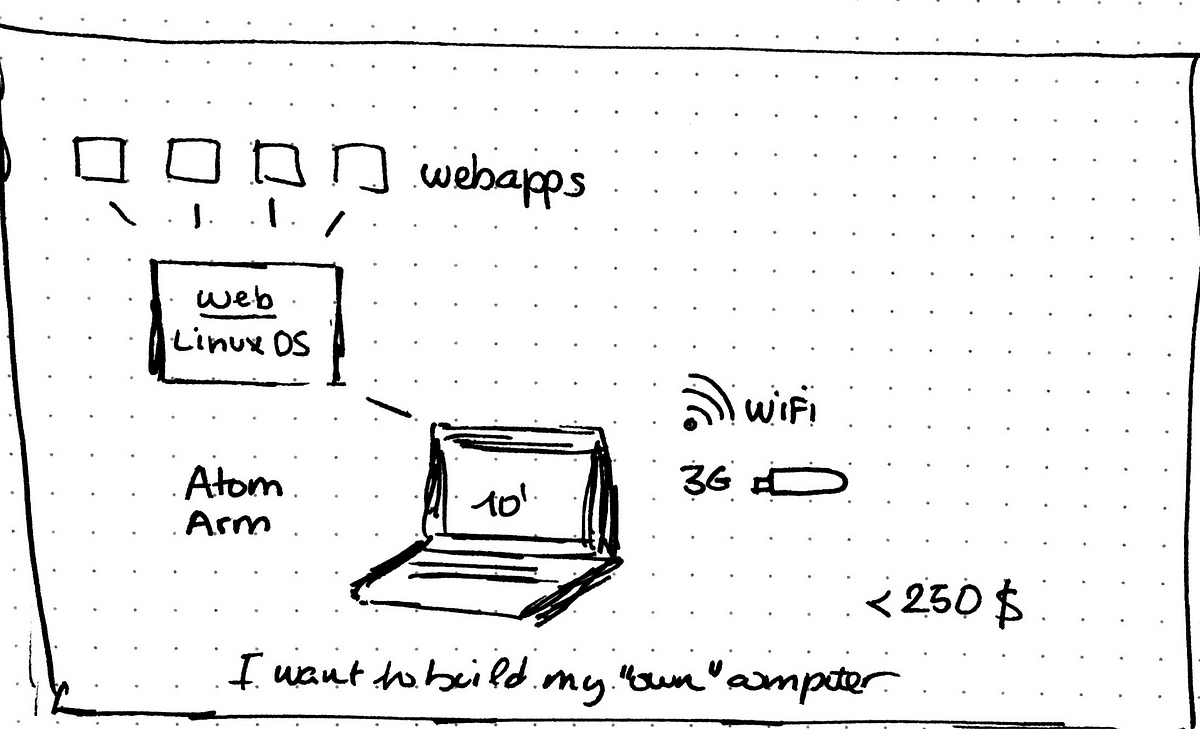

Jolicloud (2008-2015)

The Jolibook, our first product, was a star of CES 2010 in Las Vegas.

Jolicloud pioneered ethical cloud computing. Our mission: make the cloud simple and affordable for everyone. Over the years, we built a product line that set new standards. Even though Jolicloud never matched Netvibes’ traction, I’m still proud of what we built with a team of about 20 people in Paris.

Our three main products:

Joli OS

The first HTML5 cloud OS for netbooks and recycled computers. It paved the way for browser-based operating systems like Chrome OS.

Jolibook

The first personal cloud computer sold in Europe, predating Google’s Chromebook. The limited edition sold out instantly and became a collector’s item. Engadget named it one of the five best netbooks of 2010.

Jolicloud Me

A Web OS launched two years before Google’s Chromebook, with cloud sync years before Apple brought it to iOS.

I wrote a detailed story on the making of jolicloud here.

ISAI VC (2008)

My first experience in the VC world.

I was part of the founding team that designed the first version of this entrepreneurs’ fund. When the law enabling its creation changed, the fund pivoted toward more “business-centric” companies, away from the “product-centric” approach I believed in. I decided to focus on launching Jolicloud instead.

And after 2015?

I will get back soon on the second part.